Seeing . Recognising .

Some remarks on the work of Hannes Rademacher

Some remarks on the work of Hannes Rademacher

“You only see what you know,” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once stated — often quoted, and yet it remains true to this day. With this in mind, I would like to offer a few remarks for the interested viewer on the work of Hannes Rademacher. The title of the catalogue, Seeing . Recognizing., reflects precisely this idea.

Hannes Rademacher develops his works from the ground up. He stretches his canvases on self-made frames and applies the paint directly without any primer. At first glance, the paintings appear rather flat, yet in most works, the initial flatness evolves into an optical illusion: upon longer contemplation, a spatial, almost sculptural quality begins to emerge. Rademacher cultivates a visual language of geometric abstraction. Titles such as Pyramid, Rhombus, Orange-Striped Tower or Piece of Cake further emphasize this approach. His works breathe clarity, reveal consistency and order, and always maintain an acute sense for the subtle beauty and elegance of color and form.

This form of painting has almost become a hallmark of Hannes Rademacher’s art. Hard-Edge Painting, a style within abstract art, is characterized by sharp contours and flat, geometric structures. The artist’s style fundamentally emphasizes the aesthetics of order, rationality, and the beauty of pure form. His visual language demonstrates radical precision, with energy-laden edges enclosing and defining the usually few color fields — all without any visible brushstroke. The technical prerequisite for this kind of painting lies in the use of acrylic paints. For his works, Hannes Rademacher uses so-called Flashe vinyl paint — a material originally developed in the 1950s by Lefranc & Bourgeois for painting theatrical backdrops. It dries to an extremely matte, opaque finish that creates a unique surface quality. The carefully selected resins ensure that Flashe remains permanently supple and durable, while the binding agent allows the incorporation of exceptionally high pigment concentrations.

Rademacher’s process of image creation occasionally follows the principle of “guided coincidence,” which repeatedly leads him to surprising new aesthetic results. A striking example of this is the work Trompe l’Oeil (Dyckburg). During a walk, the artist was fascinated by the architectural ornamentation above the entrance portal of the chapel at Haus Dyckburg in Münster — designed by the Baroque architect Johann Conrad Schlaun. He took a photograph as a visual note and later noticed the axial shadow formations that suddenly structured the masonry. This observation inspired the division of color fields that the artist subsequently realized in his painting.

Hannes Rademacher begins his process by creating preliminary sketches, aligning dimensions and proportions with the original mass distribution, sometimes reducing their values before finally transferring them onto the canvas. He then applies the colors within their defined boundaries. In doing so, he merges the perspectival view of the existing architecture with its shadow lines into a composition where, in the end, the work evolves from flatness into a painted spatial depth — as the title itself suggests. The surface expands into space.

Rademacher continues this exploration of form and spatial depth in his more recent, small-format works. These are proportionally reduced formal elements encased in acrylic boxes, which lend them an even more pronounced aesthetic aura. They still suggest spatial illusion, yet now, through the interplay of color, they generate a positive/negative plasticity reminiscent of reliefs — inviting the viewer to engage visually and perceptually. The importance of perspective clearly asserts its place within the artist’s practice.

It is the artist’s perception — of what he sees, of what surrounds and drives him — that defines his work. Rademacher once remarked that he sees images everywhere, and that he has now found the courage to translate them into art. He appears as an artist who uses geometric forms as the primary medium of his visual language. For him, this signifies a focused contemplation of the observable world around him. Through simple geometric shapes, Hannes Rademacher explores the harmony, rhythm, and dynamism inherent in these forms — and color plays its own vital role. He confronts the calm impenetrability of one color field with the spatial depth of another.

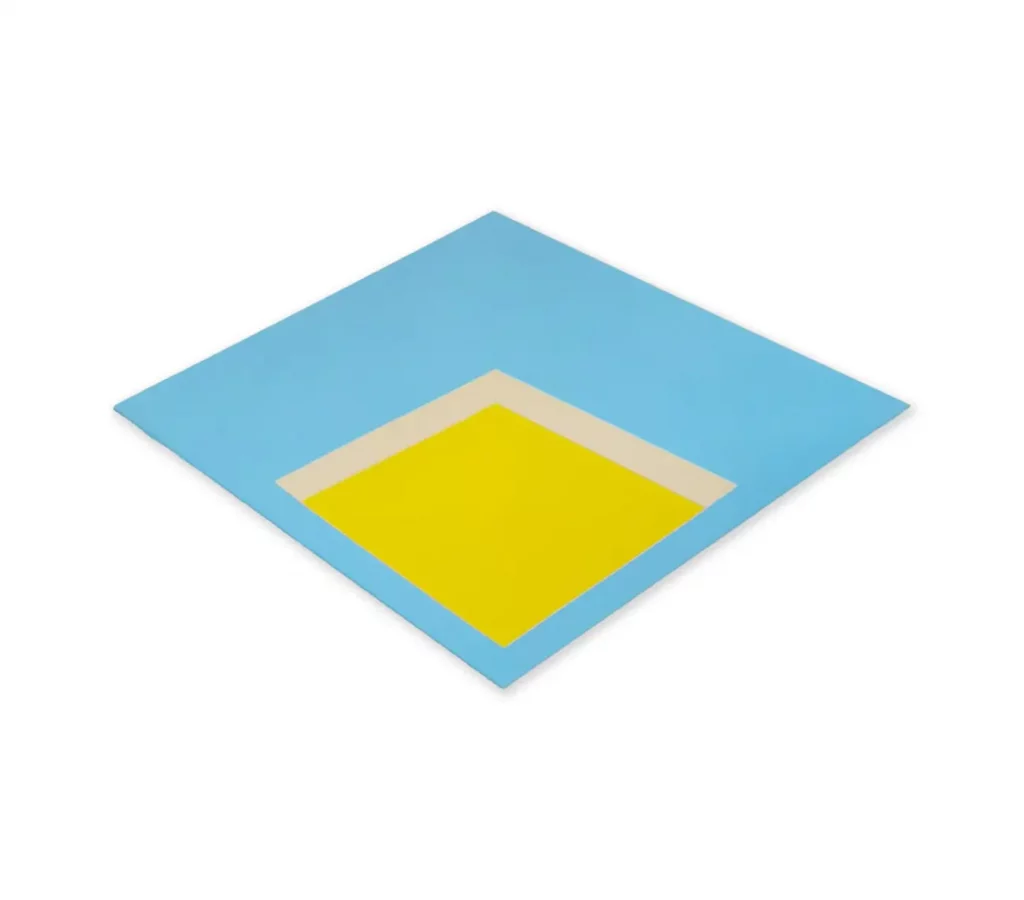

In his 2021 work Pool, the viewer may at first perceive merely a diamond-shaped, color-defined form, but upon a second look, recognize the image of a swimming pool — its yellow water surface set against the light blue of the pool’s edge, suggesting depth emerging from flatness. A similar principle applies to Simple Fold Orange – Blue (2018), where despite the underlying flatness, the viewer gains the impression of a structure folding forward. Indeed, Rademacher’s other “single” or “double fold” works demonstrate his confident command of shaping within the plane. The viewer is, in a sense, thrown back onto their own perception — onto an awareness that functions intuitively, even without prior knowledge.

One can clearly see in Hannes Rademacher’s works how he continually develops new compositions from an apparently limited vocabulary of forms and colors. In his highly sensuous, concrete art, we experience an impression of physicality and spatial depth, as he relies on the expressive power of applied color upon his constructed forms. His work is characterized by precision, clarity, and perfection. Here, we witness the strengthening of color as a space-defining element and the apparent departure from two-dimensionality.

For Hannes Rademacher, this step represents nothing less than a logical consequence. This is evident in works such as Objet trouvé (2019), where a sharply edged, elongated, smoothly worked piece of river root wood is juxtaposed with a parallel, flatter form made of rubber — both entering into a kind of relief-like dialogue, as if engaging in a dispute between nature and artificiality. A similar approach appears in White and Red Wood (2016), where wooden slats of varying lengths are connected in parallel and subjected to a strictly defined color scheme, assuming a new existence while casting an imaginary shadow of themselves onto the wall, thereby generating an additional sense of depth.

Hannes Rademacher’s art focuses on the essential elements of form, color, and space in order to evoke an immediate sensory response from the viewer. In his work, the artist engages with the underlying principles of balance, proportion, and harmony — creating spaces for contemplation and inspiration.

Michael Wessing